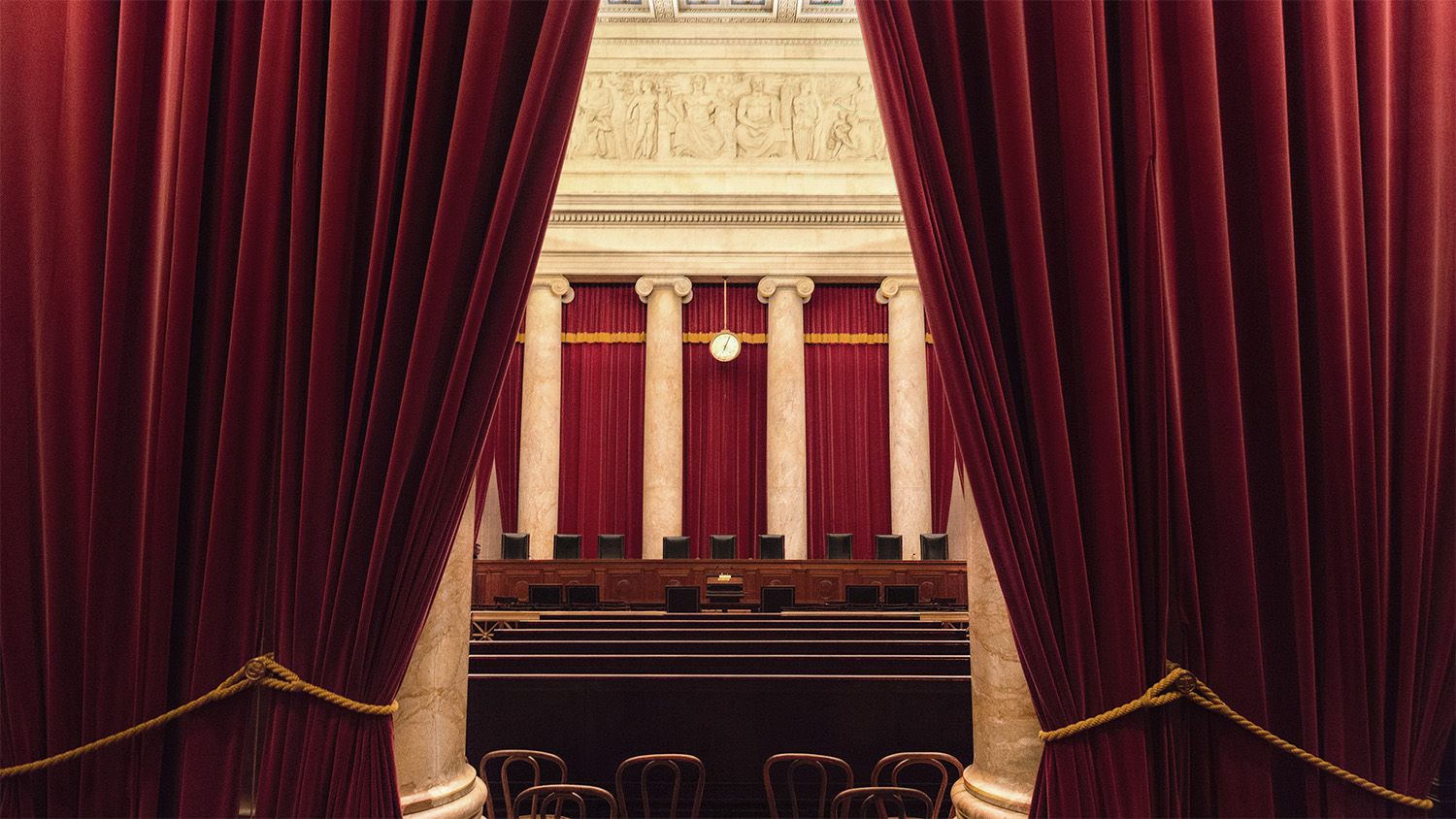

Feature Article & New Authority: The Justices’ “New Clothes”

Author: Dr. Michael H. Hoeflich

This article is featured in Volume 4, Number 11 of the Legal Ethics and Malpractice Reporter.

This month’s Feature Article and New Authority columns are combined because of the importance of the subject and the length of the commentary.

Over the past several years, the United States Supreme Court has been at the center of an ethics controversy—one that has ensnared a number of the Justices including, in particular, Justices Thomas and Alito. The LEMR has addressed the problems this has created for the Court, especially in conjunction with the series of decisions in which the Court has reversed or overruled established precedents. The growing chorus requesting the Court to adopt an ethical code finally persuaded the Court to do so on November 13 of this year, when it released the Code of Conduct for Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Unfortunately, this new Code will not lessen concerns that the Supreme Court needs serious ethics reform. Indeed, some commentators have charged that the Court has been disingenuous in adopting a code so weak that it is effectively meaningless. The Court issued the Code with the following prefatory statement:

The undersigned Justices are promulgating this Code of Conduct to set out succinctly and gather in one place the ethics rules and principles that guide the conduct of the Members of the Court. For the most part these rules and principles are not new: The Court has long had the equivalent of common law ethics rules, that is, a body of rules derived from a variety of sources, including statutory provisions, the code that applies to other members of the federal judiciary, ethics advisory opinions issued by the Judicial Conference Committee on Codes of Conduct, and historic practice. The absence of a Code, however, has led in recent years to the misunderstanding that the Justices of this Court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules. To dispel this misunderstanding, we are issuing this Code, which largely represents a codification of principles that we have long regarded as governing our conduct.

We acknowledge that this is a negotiated document resulting from consultation and debate among nine of the most powerful people in the United States. Negotiation of this sort in this highly sensitive context no doubt led to a weaker code than might otherwise have been the case. And yet, the statement remains remarkably revealing.

The Statement’s most glaring revelation is its self-justifying nature, saying that nothing in it is new, but that it is simply a “codification” of the “common law rules” the Justices already follow. There are several serious problems with this. First, it is quite clear to outsiders that there has not been consistency among the Justices as to what acts are ethical or not. Indeed, several Justices have rather flagrantly violated government-reporting rules. Second, the new Code actually appears to weaken existing restraints on the Justices’ behavior. This has the appearance of a game of “bait and switch.” Perhaps most concerning is this sentence:

The absence of a Code, however, has led in recent years to the misunderstanding that the Justices of this Court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules.

Many who read the new Code will regard this as arrogant and dismissive of what are in most cases valid concerns about some Justices’ actions.

The Code unfortunately reveals the Justices’ continued unwillingness to submit themselves to the code all other federal judges must follow. I suggest several reasons for this.

First, there is an extraordinary financial benefit to being on the Court. Justices are compensated quite generously compared even to most lawyers and judges. The Chief Justice earns $286,700 per year. The Associate Justices earn $274,200. The Justices may also earn an additional $30,000 from teaching and lectures. And there is no limit to how much they may earn from writing. This is significant because nearly everything the Justices say is of immense interest to the American public, and Justices can exploit this by producing large revenues from the publication of books and articles.

According to TIME magazine, written work by Supreme Court Justices has proved to be very profitable. TIME has reported that Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s 2021 financial disclosures revealed that she was paid $425,000 in royalties from her literary agent and that she sold a new book with a $2,000,000 advance payment. In the same year, Justice Gorsuch received a $250,000 royalty payment from Harper Collins. But the prize goes to Justice Sotomayor, who has received book royalties of $3,300,000 since 2010. While the Justices clearly have much to say to the public, they probably would not be earning such large royalties were they not on the Court.

In this context, one would expect the new Code of Conduct to impose serious limitations on the Justices’ financial dealings. Most Court watchers hoped they would, at the very least, put an end to the expensive gifts that several justices have received over the years from non-family members. Alas, they do not. Rather, a close analysis of the new Code suggests it may actually loosen such ethical restrictions on the Justices.

The new Code consists of five “canons” comprised of language that is aspirational rather than regulatory. Repeatedly, one reads that the Justices “should” or “may” do something; but they are not required to do anything. Further, if the Justices choose not to do what they “should do,” the Code provides no sanction whatsoever. Justices can do whatever they want within the bounds of the law, altogether ignore the aspirations in the new Code, and suffer no penalties whatsoever. As it stands, this Code of ethics bears no enforceability.

I recall attending the installation of a newly confirmed federal judge in New York many years ago. After I had introduced him, he stood up, approached the podium, and quoted from the film “Anna and the King of Siam”: “It is good to be king.” The audience laughed uncomfortably. After reading the new Code for the Supreme Court, I wonder if the Justices feel the same way. Indeed, historically, kings in the English tradition had more limitations placed on them, as in Magna Carta, than do the Justices of the United States Supreme Court.

The structure of the new Code is very reminiscent of the Code of Professional Conduct that preceded the current Model Rules. That document was bifurcated into aspirational canons and often-vague rules refining the canons. The Model Rules replaced it precisely because too few lawyers aspired to it. To maintain the ethical integrity of the legal profession, its overseers replaced the aspirational scheme with a regulatory one that included specific, clearly defined rules and penalties. The Justices seem to have chosen to follow the older, aspirational model in the new Code.

The new Code’s five Canons are:

CANON 1: A JUSTICE SHOULD UPHOLD THE INTEGRITY AND INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY.

CANON 2: A JUSTICE SHOULD AVOID IMPROPRIETY AND THE APPEARANCE OF IMPROPRIETY IN ALL ACTIVITIES.

CANON 3: A JUSTICE SHOULD PERFORM THE DUTIES OF OFFICE FAIRLY, IMPARTIALLY, AND DILIGENTLY.

CANON 4: A JUSTICE MAY ENGAGE IN EXTRAJUDICIAL ACTIVITIES THAT ARE CONSISTENT WITH THE OBLIGATIONS OF THE JUDICIAL OFFICE.

CANON 5: A JUSTICE SHOULD REFRAIN FROM POLITICAL ACTIVITY.

Discussions accompanying each of these canons go into greater detail. However, even these remain merely aspirational, unlike many other judicial codes of conduct and the rules of professional conduct applicable to attorneys.

The primary concerns that have led to a clamor for reform pertained to extrajudicial activities involving financial compensation, including the receipt of money and in-kind gifts, by Justices. Several provisions of the new Code seem specifically applicable to these situations. The first is Canon 2, which states that a Justice should avoid impropriety and the avoidance of impropriety. Canon 2 (B) states:

OUTSIDE INFLUENCE. A Justice should not allow family, social, political, financial, or other relationships to influence official conduct or judgment. A Justice should neither knowingly lend the prestige of the judicial office to advance the private interests of the Justice or others nor knowingly convey or permit others to convey the impression that they are in a special position to influence the Justice. A Justice should not testify voluntarily as a character witness.

Interestingly, there is no mention of accepting gifts nor an overt prohibition of allowing outside influences to affect one’s judgment. Instead, the statement uses the weaker term, “should.”

Canon 4(D)(3) deals specifically with gifts. It states:

A Justice should comply with the restrictions on acceptance of gifts and the prohibition on solicitation of gifts set forth in the Judicial Conference Regulations on Gifts now in effect. A Justice should endeavor to prevent any member of the Justice’s family residing in the household from soliciting or accepting a gift except to the extent that a Justice would be permitted to do so by the Judicial Conference Gift Regulations. A “member of the Justice’s family” means any relative of a Justice by blood, adoption, or marriage, or any person treated by a Justice as a member of the Justice’s family.

This statement is, first of all, completely aspirational. Indeed, there is something a bit shocking about the first sentence. Many observers have argued that, since there exists a set of regulations on accepting gifts that applies to all federal judges, the Justices should be subject to the same. But the statement on accepting gifts in the new code simply states that Justices “should comply” with these regulations, not that they must comply with them. Why shouldn’t the Justices be required to comply with these regulations?

The final two sentences of the statement are even more interesting. A Justice is now supposed to “endeavor to prevent any member” of his or her family from accepting gifts prohibited under the Judicial Conference regulations. Could the Court have used a weaker set of words to suggest any obligation on the part of the Justices? Indeed, at a time when the President of the United States is under investigation for his son’s alleged abuse of privilege in accepting gifts and compensation, this new statement of the Justices’ obligations seems comically weak.

While the new Code’s financial provisions give the appearance of reform, they do nothing substantive to actualize it. On the whole, it is clear that the Code’s effect is merely the codification of existing practice. It does not reform the practices Court observers and members of Congress have found problematic. That the Court would issue such a document is troublesome for several reasons.

The Rule of Law—the maxim that no person or group of persons is above the law—has stood for centuries as a foundational principle of Anglo-American law. The Justices seem to believe they should be exempt from the ethical obligations imposed on every other judge in the country. The reason is obvious. Throughout the new Code is a “presumption” that the Supreme Court Justices will simply and willingly make ethical choices. Indeed, Canon 3(B)(1) explicitly states that a Justice “is presumed impartial” in disqualification matters. Many would argue that the recent behaviors of the Justices under scrutiny prove the folly of such presumptions. That is why so many in Congress have argued for a binding ethical Code.

The new Code that the Court has issued is dangerous for the Court and the nation. Already, there has been substantial backlash. The Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, titled a recent online article, “With Its Release of a New Nonbinding Code of Conduct, the Supreme Court Fails on Ethics Again.” Commentators across the political spectrum have expressed disappointment and concern that the Court has chosen to answer its critics in this way. The danger for the Court is that this is but one more instance of the Court’s refusal to take criticisms from the public and other political branches seriously. Given the immense power that the Court wields over matters of national import, its effective dismissal of public concern over its ethical posture is gravely unwise.

The English politician Lord Acton once observed, “Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” The closest thing we have to an individual or institution having absolute power in the United States is the Supreme Court. I think it is very unlikely that the new Code will do anything to cool concerns about Justices’ behavior. Indeed, I suspect it will only add fuel to the fires of public discontent and intensify the heat for Congress to act.

READ THE FULL ISSUE OF LEMR, Vol. 4, No. 11

About Joseph, Hollander & Craft LLC

Joseph, Hollander & Craft is a mid-size law firm representing criminal defense, civil defense, personal injury, and family law clients throughout Kansas and Missouri. From our offices in Kansas City, Lawrence, Overland Park, Topeka and Wichita, our team of 25 attorneys covers a lot of ground, both geographically and professionally.

We defend against life-changing criminal prosecutions. We protect children and property in divorce cases. We pursue relief for clients who have suffered catastrophic injuries or the death of a loved one due to the negligence of others. We fight allegations of professional misconduct against medical and legal practitioners, accountants, real estate agents, and others.

When your business, freedom, property, or career is at stake, you want the attorney standing beside you to be skilled, prepared, and relentless — Ready for Anything, come what may. At JHC, we pride ourselves on offering outstanding legal counsel and representation with the personal attention and professionalism our clients deserve. Learn more about our attorneys and their areas of practice, and locate a JHC office near you.