September 2022 LEMR

FEATURED ARTICLE

Are Lawyers “Enablers”?

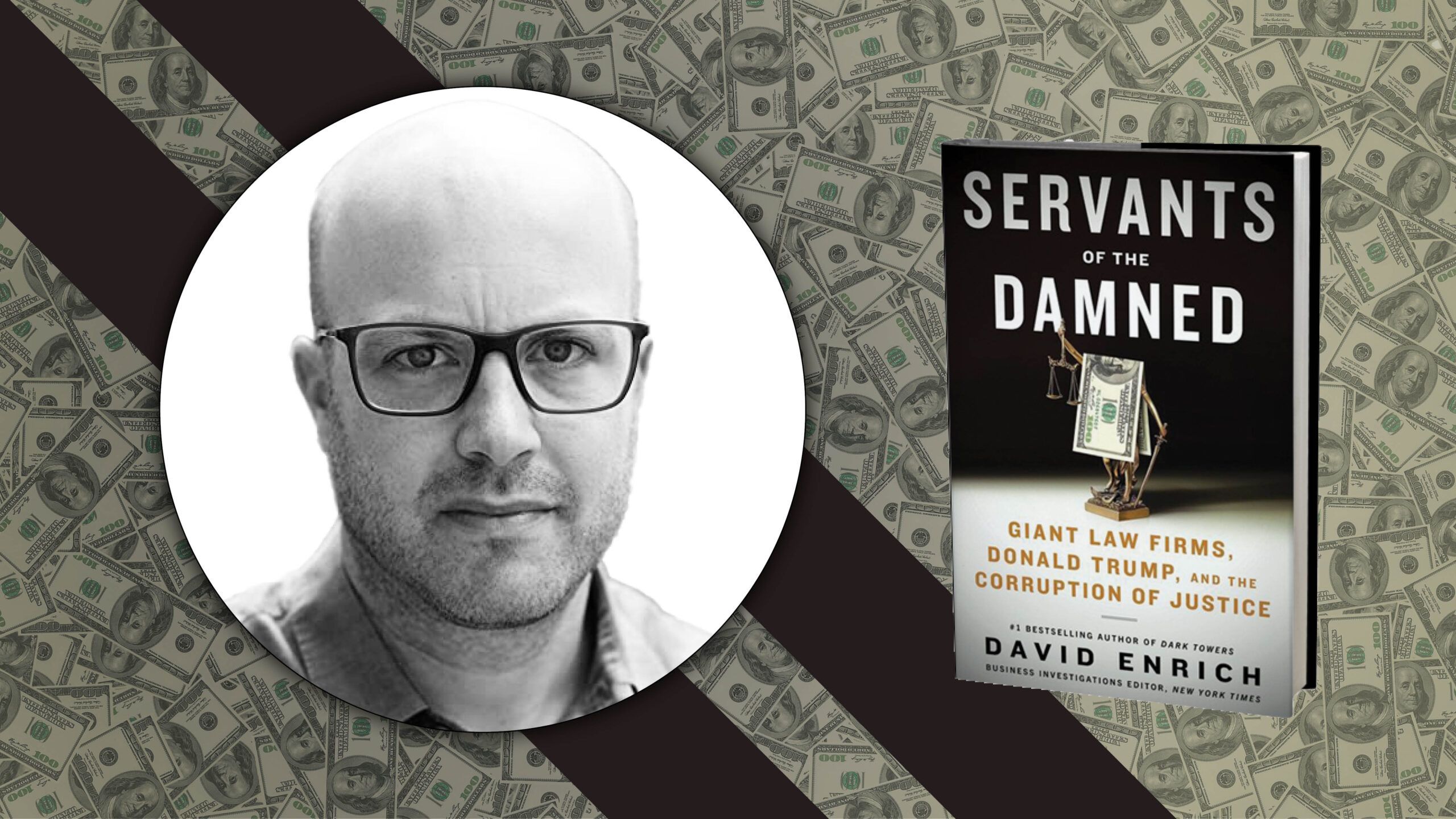

This month, David Enrich released a book called Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms, Donald Trump, and the Corruption of Justice. Enrich, who is The New York Times’ Business Investigations Editor, has produced a somewhat sensational account of the growing political and economic power of America’s largest law firms and called into question both the growing influence of these megafirms on American life and the ethical standards by which they operate. It is a book sure to evoke lively debate across the profession and the general public. While there is much in the book that one might question, it does raise some extremely important issues that all lawyers should consider.

A term Enrich introduces early in the book is particularly striking. He refers to some lawyers as “enablers” of their clients’ “bad behavior.” The term “enabler” is one that we rarely use when we discuss lawyers and their ethical duties. More often, we hear the term used in the context of addiction and codependency. But it is a thought-provoking term when applied to lawyers.

Although the lawyer-client relationship is central to the Rules of Professional Conduct, the Rules never specifically that relationship. Instead, they define various aspects of that relationship and set bounds to it. The underlying basis of the Rules is that lawyers have a fiduciary responsibility to their clients and that, above all, this responsibility manifests itself as the duty to be loyal to their clients and to maintain their clients’ confidences.

The duty of loyalty is most importantly expressed in the duty of diligence. KRPC 1.3 states:

A lawyer shall act with reasonable diligence and promptness in representing a client.

Comment 1 to KRPC 1.3 explains that:

A lawyer should pursue a matter on behalf of a client despite opposition, obstruction, or personal inconvenience to the lawyer, and may take whatever lawful and ethical measures are required to vindicate a client’s cause or endeavor. A lawyer should act with commitment and dedication to the interests of the client and with zeal in advocacy upon the client’s behalf. However, a lawyer is not bound to press for every advantage that might be realized for a client. A lawyer has professional discretion in determining the means by which a matter should be pursued. See Rule 1.2. A lawyer’s workload should be controlled so that each matter can be handled adequately.

According to this fundamental ethical rule, a lawyer “may take” whatever measures are required to represent his client’s cause within the law and ethical rules that exist. The key word here, of course, is “may.” The Comment makes it quite clear that a lawyer is not ethically required to take every step a client wishes to achieve the client’s goals but, rather, has discretion as to the means she uses to achieve these ends. Indeed, this idea is contained in the rule pertaining to scope of representation:

(a) A lawyer shall abide by a client’s decisions concerning the lawful objectives of representation, subject to paragraphs (c), (d), and (e), and shall consult with the client as to the means which the lawyer shall choose to pursue. A lawyer shall abide by a client’s decision whether to settle a matter. In a criminal case, the lawyer shall abide by the client’s decision, after consultation with the lawyer, as to a plea to be entered, whether to waive jury trial, and whether the client will testify.

(d) A lawyer shall not counsel a client to engage, or assist a client, in conduct that the lawyer knows is criminal or fraudulent, but a lawyer may discuss the legal consequences of any proposed course of conduct with a client and may counsel or assist a client to make a good faith effort to determine the validity, scope, meaning or application of the law.

KRPC 1.2.

The real question, one that is central to Enrich’s new book, is how lawyers ought to behave in the gray area of discretion permitted to them by the Rules—especially whether lawyers should use their skills and power as aggressively as possible without crossing the line into illegal or unethical behavior. Put more practically, should lawyers find ways for their clients to avoid legitimate laws that restrict their behavior? If so, how aggressive should they be in doing so? As an example of this, Enrich cites the current controversy over a technique known as the “Texas Two Step,” designed to limit corporate mass tort liability using Chapter 11 in bankruptcy.[1] Enrich is equally bothered by law firms using overly aggressive litigation to achieve openly political goals for clients.

Enrich is clearly nostalgic for a time (which may not actually have existed) when lawyers chose to decline representing clients in what they considered “dishonorable” causes as opposed to today, when some large firms will take on any representation that is not manifestly illegal or violates the Rules if the potential fees are great enough. Enrich puts it quite dramatically:

The decision to defend giant corporations for a living required you to either embrace their worldviews or to consistently subordinate your core beliefs.[2]

For Enrich, the bottom line is that some law firms have become no different from any other profit-maximizing business.

Even though one may disagree with Enrich’s concerns, the idea that lawyers have become not simply advocates for their clients, but enablers of their clients’ questionable behavior, is worth considering. So, too, is it worth considering what Abraham Lincoln wrote in a manuscript draft of a lecture on the law:

Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser — in fees, expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker, the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.

Never stir up litigation. A worse man can scarcely be found than one who does this. Who can be more nearly a fiend than he who habitually overhauls the register of deeds in search of defects in titles, whereon to stir up strife, and put money in his pocket? A moral tone ought to be infused into the profession which should drive such men out of it.[3]

Enrich quotes one lawyer who stated: “The life of a lawyer is that you defend the clients that come to you.”[4] This may well be a statement of economic reality, but it is not reflective of American ethical requirements.

Rule 1.3 and Comment 1 in particular explicitly state that a lawyer has discretion as to the means she adopts in advocating for a client. Rule 1.2(a) also makes it clear that a lawyer has the final say in choosing the means to represent a client, albeit after consultation. Further, lawyers in the United States have the liberty to refuse to represent a client for any reason—except in very limited cases, such as when a lawyer is appointed by a judge to represent a client. And, in fact, Rule 1.16 provides a justification for withdrawing from representation in certain circumstances. KRPC 1.16(b)(2) states that a lawyer may withdraw from representation if:

a client insists upon pursuing an objective that the lawyer considers repugnant or imprudent…

Given our freedom as lawyers to choose whom we represent and how we represent them, should we, in Enrich’s terms, be enablers for our clients? Should a lawyer advocate for his client by every means available, even though such means might be distasteful to us personally and expose us and our profession to the criticism that we are simply “hired guns” who care about nothing other than winning and reaping large fees?

I think that most lawyers, certainly lawyers in Kansas and Missouri, would answer this with a resounding “no.” Instead, I believe that most lawyers would endorse the notion implicit in the Rules that lawyers should not violate their personal moral codes in their practice nor should they engage in tactics such as those Lincoln condemned.

There can be no question that the practice of law is a business and that lawyers need to earn a living from their professional work. Certainly, Lincoln understood this; he was one of the highest paid lawyers of his time. But the law is more than a business; it is also a profession. And public respect and trust is an essential component of success in any profession. When I teach law students, I try to instill in them pride in the legal profession. I tell them that they should seek to earn a good living, but to do it ethically, legally, and not to compromise their own core beliefs.

The Enrich book does raise (again) an important and long-standing question. Are the Rules of Professional Conduct in need of revision to deal with the kinds of behaviors detailed in Enrich’s book? Has the role of lawyer as an “enabler” of clients’ dubious behavior gone too far in some cases? Has the profession become too much of a business and lost its sense of being more than a means to maximize personal wealth? These are questions that have arisen before, and they have broad impact.

An example of the broad impact of how far the law has become a business like investment banking, where wealth maximization is the principal goal, partially underlies the current debate whether non-lawyers should be able to invest in or own law firms. Today such non-lawyer ownership is not permitted in most U.S. jurisdictions.[5] However, there has been a strong push to change this rule. Clearly, one reason for wanting such change is the desire to increase law firm financial resources and partner profits. However, by allowing non-lawyer ownership interests in law firms, lawyers will come under increasing pressure to maximize profits and, in order to do so, push the line ethically. Such a loss of professional independence worries many in the profession. In August 2022, the ABA House of Delegates expressed its strong concern with states that might be considering changing their rules to permit such investment.[6]

In spite of the sensational nature of Enrich’s new book, it is a worthwhile read for every lawyer concerned with the future of the legal profession. It has been much on my mind this week as I taught a group of first year law students. In the first weeks of the semester, I deliberately spend time talking to my students about the long, proud history of the law and lawyers and of the importance of law and lawyers to maintaining the republic which we are all blessed to be part of. I reassure them that, with a bit of luck and hard work, they will have successful careers as lawyers and that it will provide them and their families with economic security. But I also tell them that the law as a profession will give them something as important: the conviction at the end of the day that they are engaged in something worthwhile and greater than themselves. I should hate to think that someday it will be impossible to say such things to my students.

Read this month’s edition of LEMR

References:

- D. Enrich, Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms, Donald Trump, and the Corruption of Justice (2022), p. 305.

- Ibid., p. 93.

- “Abraham Lincoln’s Notes for a Law Lecture.”

- D. Enrich, Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms, Donald Trump, and the Corruption of Justice (2022), p. 101.

- See, R. Minkoff, “Looking for Trouble and Finding It: The ABA Resolution To Condemn Non-Lawyer Ownership,” Professional Responsibility Law Blog (August 16, 2022).

- This would be a change to Rule 5.4 which prohibits lawyers from sharing fees with non-lawyers; but, see, J. Henry & B. Love, “Change Is Coming: Despite ABA Vote, Law Firms Will Face More Rivals Outside the Legal Industry,” in LawBlog.com (August 10, 2022).

About Joseph, Hollander & Craft LLC

Joseph, Hollander & Craft is a premier law firm representing criminal, civil and family law clients throughout Kansas and Missouri. When your business, your freedom, your property, or your career is at stake, you want the attorney standing beside you to be skilled, prepared, and relentless. From our offices in Kansas City, Lawrence, Overland Park, Topeka and Wichita, our team of 20+ attorneys has you covered. We defend against life-changing criminal prosecutions. We protect children and property in divorce cases. We pursue relief for victims of trucking collisions and those who have suffered traumatic brain injuries due to the negligence of others. We fight allegations of professional misconduct against doctors, nurses, judges, attorneys, accountants, real estate agents and others. And we represent healthcare professionals and hospitals in civil litigation.